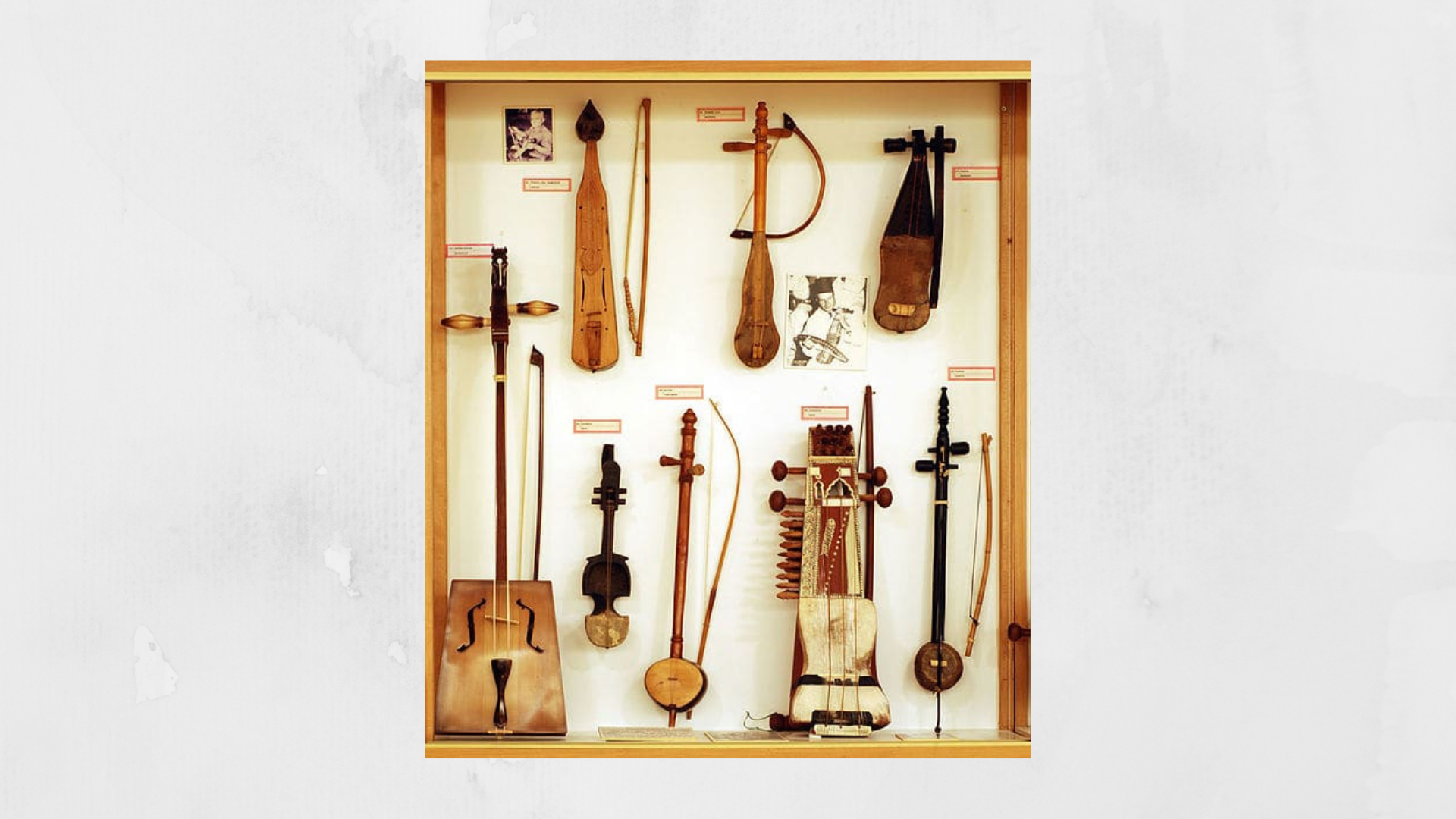

Bowed string instruments have been played all over the world for many thousands of years.

Medieval instruments including the Chinese erhu, the Finnish bowed lyre and the Indian sarangi all had the same basic mechanics as the modern violin, using the principle of a continually resonating string amplified by a hollow body.

In 7th century Greece, there was an instrument called the kithara, a seven stringed lyre, the features of which were very different from the violin.

Early Origins

The development of a musical instrument is rather like the process of evolution. It is gradual and complex, with many of its stages indistinct or undocumented. The history of the violin can be traced back more or less to the 9th century.

One plausible ancestor for the violin is the rabãb, an ancient Persian fiddle which was common in Islamic empires. The rabãb had two strings made of silk which were attached to an endpin and tuning pegs.

These strings were tuned in fifths. The instrument was fretless, its body made from a pear shaped gourd and a long neck.

It was introduced to Western Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, and the influence of both the rabãb and lyre, along with a constant search for perfection and refinement and the demands of increasingly complex repertoire, led to the development of various European bowed instruments.

Ancestors of the Violin

Forerunners of the violin include the rebec, an instrument based on the rabãb, which appeared in Spain, most likely as a result of the Crusades.

The rebec had three strings and a wooden body and was played by resting it on the shoulder.

There were also Polish fiddles, the Bulgarian gadulka and Russian instruments called gudok and smyk, which are portrayed in frescos from the 11th century.

The 13th century French vielle was very different from the rebec. It had five strings and a larger body, which was closer in shape and size to the modern violin, with ribs shaped to allow for easier bowing.

Confusingly, the name vielle later came to refer to a different instrument, the vielle á rue, which we know as the hurdy-gurdy.

Emergence and Early Variants

There is no reference to the word violin until the reign of Henry VIII, but something very much like the violin existed, and its name was fydyl.

This instrument was played with a fydylstyck, proof that it was bowed and not plucked.

It had only three strings and a fretless fingerboard, and it was used for dancing, in banquets and social events; occasions which required an instrument with a strong sound, held shoulder height for projection.

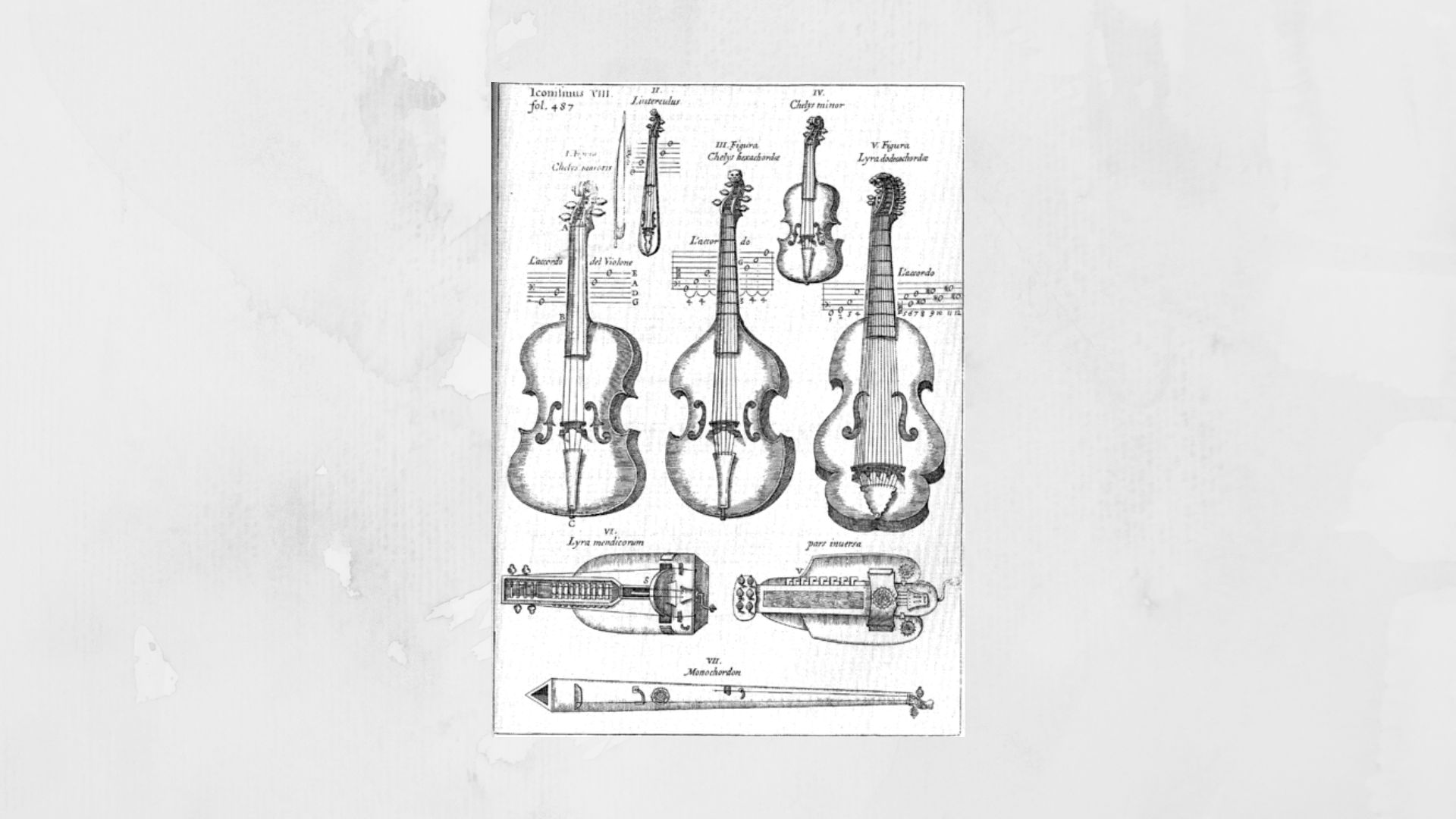

In 15th century Italy, two distinct kinds of bowed instruments emerged. One was fairly square in shape and held in the arms and was called a lira da braccio or viola da braccio, meaning viol of the arm.

This instrument had three strings and was the same general size and shape as the vielle, but the C-shaped sound holes in the body had been replaced by the now familiar F-holes.

The other bowed instrument was a viola da gamba, meaning viol for the leg.

The Rise of the Modern Violin

These gambas were important instruments during the Renaissance period, but were gradually replaced by the louder instruments of the less aristocratic lira da braccio family as the modern violin developed.

The violin first appeared in the Brescia area of Northern Italy in the early sixteenth century.

From around 1485, Brescia was home to a school of highly prized string players and famous for makers of all the string instruments of the Renaissance; the viola da gamba, violone, lyra, lyrone, violetta and viola da brazzo.

The word violin appears in Brescian documents for the first time in 1530, and whilst no instruments from the first decades of the fifteenth century survive, violins are shown in several paintings from the period.

Violins vs Viols

The first clear description of the violin, depicting its fretless appearance and tuning, was in the 1556 Epitome Musicale by Jambe de Fer.

By this time the violin had begun to spread throughout Europe. It was mainly used to perform dance music but was introduced into the upper classes as an ensemble instrument.

Where the viol, which was preferred in aristocratic circles, had been perfect for contrapuntal music and for accompanying the voice, the violin was normally played by professional musicians, servants and illiterate folk musicians.

| "The violin is very different from the viol. First, it has only four strings, which are tuned at a fifth from one to the other, and each of the said strings has four pitches in such wise that on four strings it has just as many pitches as the viol has on five.

It is smaller and flatter in form and very much harsher in sound, and it has no frets because the fingers almost touch each other from tone to tone in all the parts. Why do you call the former Viols, the latter Violins? We call viols those upon which gentlemen, merchants, and other persons of culture pass their time.The Italians call them "viole da gambe,” because they hold them at the bottom, some between the legs, others upon some seat or stool; others [support them] right on the knees of the said Italians, [but] the French make very little use of this method. The other kind [of instrument] is called "violin", and it is this that is commonly used for dance music [dancerie], and for good reason: for it is easier to tune, because the fifth is sweeter to the ear than the fourth is" It is, also easier to carry, which is a very necessary thing, especially in accompanying some wedding or mummery. The Italian calls it "violon da braccia" or "violone" because it is held upon the arms, some with a scarf, cord, or other thing. I did not put the said violin in a diagram, for you can consider it upon [the one for] the viol, joined [to the fact] that few persons are found who make use of it other than those who, by their labour on it, make their living." - Jambe de Fer from the Journal of the Viola Da Gamba Society of America, November 1967. |

The Evolution of the Modern Violin

The viola and cello developed alongside the violin in early 16th century Italy. This new family of stringed instruments gradually took the place of the gambas and viols as new ideas of sound emerged.

It is commonly accepted that the first modern violin was built by Andrea Amati, one of the famous luthiers (lute makers) of Cremona, in the first half of the 16th century.

The first four-stringed violin by Amati was dated 1555 and the oldest surviving of his instruments is from around 1560, but between 1542 and 1546, Amati also made several three-stringed violins.

Amati built his violins using a mould, which meant the measurements became much more precise. He developed a more vaulted shape for the body of the instrument rather than the flat soundboards of the early stringed instruments.

It is speculated that Amati may have studied with Gesparo da Salo in Brescia, but some records show that he was well established in Cremona long before he began making violins, and was in fact older than da Salo.

The Brescian school of luthiers had existed for 50 years before violin making began in Cremona, but the Cremona school gained prominence after 1630, when the bubonic plague swept Northern Italy and eliminated much of the Brescian competition.

Italy had managed to avoid the thirty-year war and development of the instrument continued in a golden age of culture.

Andrea Amati mastered many apprentices, and produced a dynasty of violinmakers, including the Guarneris, Bergonzis, and Rugeris.

His own sons followed him into the trade, and his grandson, Nicoló Amati, the most famous Amati, trained Antonio Stradivarius.

Stradivarius made over 100 instruments, of which roughly two thirds survive. His violins are some of the most imitated by modern makers today.

18th and 19th Century Transformations

The violin, originally an instrument of the lower classes, continued to gain popularity, becoming integral in the orchestra during the seventeenth century as composers such as Monteverdi began writing for the new string family.

The instrument continued to develop between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, and the surviving historic violins have all undergone alterations.

The violin bow changed dramatically in around 1786, when Françoise Xavier Tourte invented the modern violin bow by changing the bend to arch backwards and standardising the length and weight.

The violin fingerboard was lengthened in the 19th century, to enable the violinist to be able to play the highest notes. The fingerboard was also tilted to allow more volume.

The neck of the modern violin was lengthened by one centimetre to accommodate the raising of pitch in the 19th century and the bass bar was made heavier to allow for greater string tension.

Where classical luthiers would fix the neck to the instrument by nailing and gluing it to the upper block of the body before attaching the soundboard, the neck of the modern violin is mortised to the body once it is completely assembled.

By the 18th and 19th century the violin had become extremely popular. By the late 18th century, makers had begun to use varnished developed to dry more quickly.

This had an impact on the quality of instruments produced. The quality of the wood used in violin making has been affected by the lack of purity of modern water as nearly all substances dissolved in water permanently penetrate wood.

By the 19th century violins were being mass-produced all over Europe. Millions were made in France, Saxony and the Mittenwald, in what is now Germany, Austria, Italy and Bohemia, now part of the Czech Republic.

It is partly for this reason that the violins of the early Italian masters are so prized, so well regarded and so expensive. A Stradivarius violin will now sell for many millions, the most expensive so far on record sold for $16million in 2011.

Modern Violins

More recently, new violins were invented for modern use. The Romanian Stroh violin used amplification like that of a gramophone to boost the volume.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, before electronic amplification became common, these violins with trumpet-like bells were used in the recording studio where a violin with a directional horn suited the demands of early recording technology better than a traditional acoustic instrument.

Electric and electro-acoustic violins have also been developed. An electro-acoustic violin may be played with or without amplification, but a solid bodied electric violin makes little or no sound without electronic sound reinforcement.

Electric violins can have as many as seven strings and can be used with equalisers and even sound effects pedals, a far cry from the exacting acoustic knowledge which created the great violins of the Italian Renaissance.

violin and ageViolin an

The beneficial effects of learning a musical instrument are well documented in young children, and the violin has seen its share of child prodigies, but how does the relationship with the instrument change as the player gets older, and is it ever too late to start learning?

The beneficial effects of learning a musical instrument are well documented in young children, and the violin has seen its share of child prodigies, but how does the relationship with the instrument change as the player gets older, and is it ever too late to start learning?

Even the youngest children will respond to music. Shinichi Suzuki, Japanese violinist and father of the Suzuki method of teaching, tells a story in his book Nurtured by Love, about a five-month-old baby called Hiromi.

Hiromi had grown up listening to her older sister learning the violin, and her sister had been practising the Vivaldi A-minor concerto. Suzuki recalls, “When everyone was quiet, I started playing a minuet by Bach. While I played, my eyes did not leave Hiromi’s face. The five-month-old already knew the sound of the violin well, and her eyes shone while she listened to this piece that she was hearing for the first time. A little while later, I switched from the minuet to the Vivaldi A-minor concerto, music that was played and heard continuously in her home. I had no sooner started the piece when an amazing thing happened.

“Hiromi’s expression suddenly changed. She smiled and laughed, and turned her happy face to her mother, who held her in her arms. “See – that’s my music,” she unmistakeably wanted to tell her mother. Soon again, her face turned in my direction, and she moved her body up and down in rhythm.”

Suzuki’s method of teaching the violin begins in infancy. Based on the observation that every child is fluent in his or her own language, Suzuki believed that ability is not a matter of inherited talent, but of correct teaching, environment and encouragement.

According to Carolyn Phillips, former Executive Director of the Norwalk Youth Symphony Orchestra, learning music in childhood helps develop the areas of the brain which are involved in language and reasoning. Musical training physically develops the part of the left-brain that is known to be involved with language. It also increases the capacity of the memory. The parts of the brain that control motor skills and memory actually grow.

Phillips also explains in her article, Twelve Benefits of Music Education, that there is a causal link between music learning and spatial intelligence, which is the ability to perceive the world accurately and to form mental pictures of things.

Children who learn a musical instrument have been proven to be better creative learners and problem solvers. In his book Always Playing, Violinist Nigel Kennedy, former enfant terrible of the Classical Music world, describes his feelings about his early schooling: “I guess something like 80 per cent of what I was formally taught at my schools, particularly at the Menuhin [School], I reacted to badly, but that reaction led me to trying my own alternatives and it is always such a buzz when you see your thinking work out.”

Music also gives the player an internal glimpse of other cultures and teaches empathy with people from those cultures. Every piece of music has a cultural and historical back-story. When children come to understand different cultures through music, their development of empathy and compassion, rather than a selfishly orientated motivation, provides a bridge across cultures and leads to an early respect for people of different races.

Learning an instrument teaches the value of sustained effort. It teaches teamwork, responsibility and discipline. In an ensemble of any size, players must work together for a common goal and commit to turning up to rehearsals on time, having prepared the music. This requires time management, organisational skills and social skills, a focus on doing rather than simply observing and a willingness to conquer personal fears and take risks.

Most of all, learning a musical instrument is a means of self-expression. In Western society the basics of existence are fairly secure. The challenge is to make life meaningful and to reach for a higher state of development. Every human being needs at some point in his or her life to be in touch with his core, with what he is and what he feels. Having an outlet for self-expression leads inevitably to higher levels of self-esteem.

A child will start learning the violin for many reasons, but the violin is an instrument that can appeal greatly. It is small and lightweight, immediately accessible and available in different sizes so even a tiny child can pick up his violin easily. The violin is also a very personal instrument. Each violin looks similar, but no two sound the same, and even the same violin played by two people will sound different. This physical attraction to the violin is what leads a small child who has just begun learning to take his violin to bed with him like a teddy bear.

The violin is also an instrument that seems to attract child prodigies. Mozart was a child prodigy, as were Menuhin, Zukerman, Perlman and so many others. The pressure on these children can be enormous. Many don’t have normal childhoods. Paganini was apparently often locked in his room for hours by his father and forced to practice; a discipline which led him to serious problems with alcohol by the time he was 16.

Child “genius”, violinist Chloe Hanslip, interviewed in the Telegraph in 2007, commented, “I couldn’t be a normal child. Not properly normal, because I’m a classical violinist.” In the same article, Jennifer Pike, who won the BBC Young Musician of the Year on violin in 2002, aged just 12, explained in a more balanced way that an intensive musical education doesn’t suit everybody.

This comment is borne out by the experiences of Julian Rachlin, who won the Eurovision Young Musician of the Year in 1988, when he was 13. He went on to become the youngest ever soloist to perform with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. By the time he was 20, Rachlin had lost his confidence so badly it nearly ended his career. He went to study with Pinchas Zukerman, himself a former child prodigy. Zukerman helped him understand he had to develop his career path at his own pace.

Although in the instance of child prodigies, the motivation for progress often comes from the child, the conventional view is that they often end up as adults with broken lives and unfulfilled dreams. The American violin virtuoso, Itzhak Perlman, said in an interview with the New York Times that many things could go wrong with prodigies, particularly those whose parents had suspect agendas, that is, they wanted to achieve success through their child.

Shinichi Suzuki had a poor view of such parents. In Nurtured by Love he tells the story of a child whose mother had come to him with the question, “ Will my child amount to something?” Suzuki felt this was an offensive question and replied, “No. He will not become ‘something’.” He explains, “It seems to be the tendency in modern times for parents to entertain thoughts of this kind. It is an undisguisedly cold and calculating educational attitude.”

Suzuki told the child’s mother, “He will become a noble person through his violin playing… You should stop wanting your child to become a professional, a good money earner... A person with a fine and pure heart will find happiness. The only concern for parents should be to bring up their children as noble human beings. That is sufficient. If this is not their greatest hope, in the end the child may take a road contrary to their expectations. Your son plays the violin very well. We must try to make him splendid in mind and heart also.”

The ideal, as Julian Rachlin found, is that musical development should compliment personal growth; that is, not just educational growth but the development of the whole person. The relationship with creativity is intrinsic to the relationship with the self. As one grows, the other will become surer.

Watch this video of 11-year-old Sirena Huang, presenting a TED Talk on the technology of the violin, in between beautiful, accomplished performances. She has worked very hard to reach this level, but the main aspect that shines through is her enjoyment of what she is doing, and the need to share it; the fundamental human need to communicate.

A child might begin the violin because he likes the sound, knows someone else who plays or because his parents decide he should learn. But what if you are considering learning as an adult? Is it too late?

In her book Making Music for the Joy of It, Stephanie Judy sets out to encourage adult beginners. The first sentence in the book reads, “Welcome! You’ve chosen a wonderful time to start making music.”

Judy explains, “As an adult beginning musician you have many advantages over a child in the same situation. Your primary advantage is that you are in charge…Maybe you’ll regret that you didn’t start sooner, but that regret is a pale rival to your freshness and enthusiasm. You are not just fulfilling a personal fantasy; you are answering a great human longing.”

The most important prerequisite to beginning the violin later in life is to feel at ease with making music. Many adult beginners feel awkward and overwhelmed by the physical challenge of learning, but feeling at ease has more to do with clearing away self-doubts than it does with holding the instrument. Once you begin to get rid of doubts about your musical self, you have cleared the path for progress.

This is not only true for beginners, it is very pertinent for players who have been playing for many years, perhaps since childhood, but whose relationship with their instrument has always been guided by someone else; a teacher or a parent. Even at a professional level, as a violinist continues to develop, old self-doubts must be cleared in order to free the way for new musical expression and integrity. This then begins to work in the other direction. As you begin to understand your musical and creative self and free up mental blocks, this understanding transfers in a positive way into other aspects of your life. Even at a professional level, a violinist never stops learning.

As an adult beginner you may feel you should have started as a child, but the fact is, for whatever reason, you didn’t. It’s also true that all your experience to this point in your life has brought you to wanting to play. You must begin where you are today.

Playing the violin is a holistic activity. It involves the whole body but also the deeper self, self-doubt and complex experiences and emotions.

Judy says, “Adults often help themselves along the road of musical understanding more quickly than children because of their deeper experiences, both of music and of life.”

The reasons an adult might want to start learning the violin are very different from the reasons a child might have. Adults often get to a point where they want something that makes new demands on them. Sometimes it’s a need to express artistic energy and communicate. It can be a yearning for some activity that needs total mind and body focus, total involvement in a world where we constantly multitask. Learning the violin can offer stress relief and perspective as the music draws you into the present moment. It is a social activity, with the chance to play fantastic orchestral and chamber music repertoire at any level.

Whatever age you are, five or 75, the important ingredients to success are the same: Passion, patience, time to practice and perseverance. We would never ask if it is too late to learn to paint, or to learn a language yet somehow there is a belief that unless you begin the violin as a toddler it is too late. Not so. There is an enormous benefit to engaging the brain in new activities throughout all the stages of life.

Here is an example from www.uncorneredmarket.com, from a selection of inspiring stories for elderly people.

“You are never too old to learn.

Andrew, one of my grandfather’s colleagues from when they both worked in India in the 1960s, now lives in my grandfather’s retirement complex.

He had to give up his violin lessons when he escaped Hungary in 1937 as his family began facing persecution for being Jewish.

“It had been 75 years since my last violin lesson. I wanted to play violin again, but I sounded awful. I decided I needed lessons.”

Earlier this year, he began taking violin lessons again. We asked how things are going.

“I’m progressing pretty well. It’s fun to play again,” Andrew chuckled.

He’s scheduled to play a Christmas concert this week. I imagine there are many more in his future, too.”

Finally, whatever your age, it’s important to maintain your physical wellbeing in order to keep playing at your best. Read the article on the body for some ideas and tips.

Never practice without warming up, and take regular, gentle exercise such as yoga to keep your joints mobile. The DVD Yoga for Musicians shows some simple and effective stretches to release tension and build muscle tone.

The British Association for Performing Arts Medicine has lots of information about health resources for musicians on their website, including a useful chart of warm up exercises.

So whatever your age, keep playing, keep learning and keep enjoying all that the violin has to offer.